Music is made expressive and exciting and emotional by the skillful use of contrasts by its performers. Music that is all loud or all soft, for example, becomes sterile and boring, while music that builds to climaxes and retreats into serene quiet is highly expressive. One area of music that relies on contrast is that of accents. By definition, when something is accented it is made to stand out from what is around it. Words have accented syllables. To pronounce a word properly, one syllable is given more weight or stress than the others. For example, if I say, “I enjoy my morning COFfee, you would think nothing amiss. But if I say, “I enjoy my morning cofFEE, then you’d rightly think that my pronunciation of “coffee” sounded peculiar. Worse yet, if I accented neither syllable, it would sound like the worse computer monotone we’ve ever heard. Accents make part of something stand out.

In music, accents show us which notes in a phrase are the most important. They also indicate what the style of music is that we’re hearing. “My Favorite Things” sung by Mary Martin on Broadway in The Sound of Music sounds very different from John Coltrane’s legendary recording of the same song. Why? Because Coltrane plays jazz with it, accenting things that the Broadway actresses never do.

But there is more to musical accents than just that. This is because there are several different kinds of accents in music. For our purposes, let’s agree that there are three categories of accents, and five types of accents. The categories are dynamic, agogic, and tonal.

Categories of Accents

Dynamic accents are what many musicians play when they see an accent marked in their notated music. The musician sees a “greater than” sign ( > ) over or under a note, and they respond by making that note louder than the others. Sometimes, this type of accent is referred to as a “stress accent,” because performing it places stress or emphasis on the note. A good example of this category of accent is “Overture to Candide” by Leonard Bernstein. Notice at 40 seconds in how he uses dynamic accents. You can even see him indicating them in his conducting.

Agogic accents are made not by playing the note louder, but by playing it longer. Among a group of notes in a phrase, the one that is relatively longer than the others tends to be heard as accented. It’s like a very tall person who stands out in a crowd of otherwise shorter people. The tallest person can help but stand out in the crowd. Agogic accents are not as obvious as dynamic accents. The longer notes in a phrase just stand out because of their duration, without really calling attention to themselves. They don’t shout at you, they just get your attention with a whisper. Listen to this performance of Frank Ticheli’s arrangement of the American folk song “Shenandoah,” and notice how the shorter notes just lead into those longer notes, respectfully pointing them out. Another good example is Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things.” In that recording, Coltrane uses elongated notes to great effect, creating metric syncopation.

The third category of accents is tonic accents. Tonic accents should not be confused with the tonic note of a musical scale or key. In that case, tonic is the first note of a scale, or the home key of a musical work. Tonic accents, on the other hand, take their name from the adjective that refers to tension, from the Greek word “tonics,” or stretching, from the Greek word tonos. Tonic accents are those which distinguish a note by being higher in pitch than the notes around it. They literally jump out at you by being so much higher. An example of tonic accents is “Hens and Cockerals” from The Carnival of the Animals by Saint Saens.

Types of Accents

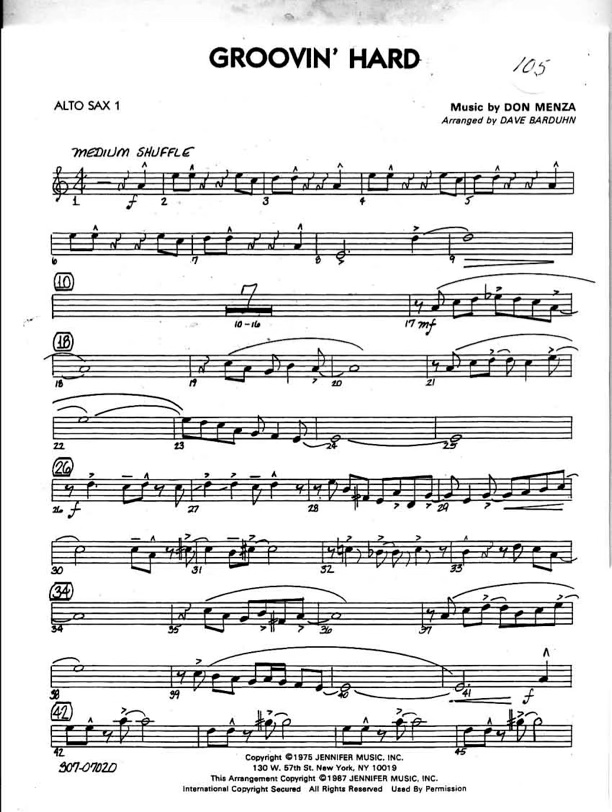

Those are the categories of accents. Within the categories there are types of accents. Each type has its own symbol that is found in musical scores and instrument and vocal parts. The most common of these symbols is the “greater than” sign ( > ), which I mentioned earlier. Accents of this type are often used to create syncopations, which are instances of notes that ordinarily are weak being made strong. This type of accent is found often in jazz. Look at this Alto Sax part from an educational arrangement of “Groovin Hard.” In measure 17, you’ll see this type of accent under a slur. This tells the musician to play those notes louder but without articulating. Later on in the piece, at bar 32, you’ll find those same type of accents, but this time there is not slur. The musician will play them louder for the accent, but will also articulate each one, and with more of an “attack” than if the note had no accent indicated.

If you look at the very first line of printed music, you’ll see another type of accent, These are called marcato accents. They are indicated by a carat ( ^ ) over the note. This type of accent again is played louder and is articulated with extra “attack,” but a shortened duration is added. These marcato accents are not only louder, they are also shorter and more abrupt than the “greater sign” accents.

Staccato accents are marked with a dot over or under the note. This dot is not to be confused with a dot that is placed next to a note, on its right, which lengthens the duration by fifty percent. The dot over or under the note is called staccato, and it means to leave a space between that note and the next one. Staccato accents are not necessarily short, but they must be shortened so that there is a silence before the next note. That silence interrupts the sound enough to call attention to the note, making it a type of accent. A related accent type is the staccatissimo accent. This note must be very short. It isn’t just leaving a space after the note, it is making the note extremely short. This type of accent is marked with a triangle over the note pointing down at it. These staccassimo accents are not as common as the other types.

Lastly, there are tenuto accents. This type of accent is akin to agogic accents in that they have to do with note length. These accents don’t occur by lengthened notated durations, but inste by an expressive lengthening of the duration, but still within the limits of the note value being accented. Tenuto accents can come right up to the limit of slowing or even pausing the forward motion of the music, but never quite stop the momentum. They are usually used as an expressive gesture in slower, more lyrical passages.

Conclusion

One final point on all accents. The exact interpretation of an accent will be to some extent influenced by the style of music being played. Jazz marcato accents are not performed exactly the same as they are in classical music, and are more rare in pop and rock styles Tenuto accents are very common in jazz, used in combination with staccato accents, but are unusual in rock music. In any musical style, accents, if overused, cease being accents at all. Remember or one tall person in a crowd. I said he was like an accent, standing out. But if everyone around him in that crowd were as tall as he, then he would no longer stand out in the crowd. So it is with accents. If everything is accented, then nothing is accented. The best way to know how to play or sing a particular accent is to listen to professional recordings of that style of music, and learn what the pros do.